|

|

Grzegorz Sztabiński »

ZAKRYCIE PRZESUNIECIE ZNIKANIE

About a certain process with an image

disappearing in the background

of knowledge about existence, the knowledge attained

through rational construction or irrational intuition and

expression. Grzegorz Sztabiński is undoubtedly the one

who represents the first attitude. The analyses of his

work often emphasize that it is dominated by rational-

-comprehensive way of thinking. It seems obvious, if we

take into consideration the fact that the artist is a philosopher

– practitioner and in his works he looks for visual

counterparts of the general universal content, namely

the relation of the whole to its parts, mutual relations

of: constancy and variability, linear duration and cyclic

occurrences, the opposition of: chaos – cosmos, duration –

change, visibility – invisibility.

The results of subsequent creative activities increase his

experience, and some specific elements (image motives

– primal and transformed, objects and their reflections

preserved in a variety of visual media) enter the area

of the artist’s thought and imagery space, they are

further consistently contested and transformed, forming

and initiating an infinite sequence of activities. The

continuation, the lack of the concrete which could be

defined as an individual work of art is the equivalent of

intellectual reflections evoking the successive steps.

Accentuating the aspect of processuality, the lack of

orientation towards uniqueness and finiteness of a work

of art is most easily associated with the tradition of

Conceptual Art. The artist, however, is rather more willing to

accept the definition of his approach as Post-Conceptual.

In his visualisations images, installations are not only

a counterpart or an expression of the essential, most critical

mental factor, but also a necessary element of the whole

process, as the stages of introducing order (an attempt to

find it and to express it) and destruction – as a modification

of the rules accepted before – take place in the domain of

the sensual factor necessary here, and the artist can not go

without them, as in the case of – sometimes only virtual –

records of methods of a few conceptual artists.

Is not Grzegorz Sztabiński’s work a perpetual assurance

(self-assurance) of the intuition that an image (regarded

as an object externalization of the mental process) is an

essential element of art?

Following the successive stages of the artist-philosopher’s

creation we can observe a characteristic aspect: the

evolution of the image as an element which is subject

to a variety of destructive impacts (distortions being

a result of geometric transformations, multiplications

[repetitions], obscuring and blurring its representation up

to blackout planes used to cover it) and which nevertheless

importunately recurs. Not only in the works on a plane or in

spatial installations, but also during performance actions.

And in the latter the ‘annihilation’ of the image was not

successful. It seems that the artist will probably have to

accept the fact that the image, despite a continuous fight

of knowledge about existence, the knowledge attained

through rational construction or irrational intuition and

expression. Grzegorz Sztabiński is undoubtedly the one

who represents the first attitude. The analyses of his

work often emphasize that it is dominated by rational-

-comprehensive way of thinking. It seems obvious, if we

take into consideration the fact that the artist is a philosopher

– practitioner and in his works he looks for visual

counterparts of the general universal content, namely

the relation of the whole to its parts, mutual relations

of: constancy and variability, linear duration and cyclic

occurrences, the opposition of: chaos – cosmos, duration –

change, visibility – invisibility.

The results of subsequent creative activities increase his

experience, and some specific elements (image motives

– primal and transformed, objects and their reflections

preserved in a variety of visual media) enter the area

of the artist’s thought and imagery space, they are

further consistently contested and transformed, forming

and initiating an infinite sequence of activities. The

continuation, the lack of the concrete which could be

defined as an individual work of art is the equivalent of

intellectual reflections evoking the successive steps.

Accentuating the aspect of processuality, the lack of

orientation towards uniqueness and finiteness of a work

of art is most easily associated with the tradition of

Conceptual Art. The artist, however, is rather more willing to

accept the definition of his approach as Post-Conceptual.

In his visualisations images, installations are not only

a counterpart or an expression of the essential, most critical

mental factor, but also a necessary element of the whole

process, as the stages of introducing order (an attempt to

find it and to express it) and destruction – as a modification

of the rules accepted before – take place in the domain of

the sensual factor necessary here, and the artist can not go

without them, as in the case of – sometimes only virtual –

records of methods of a few conceptual artists.

Is not Grzegorz Sztabiński’s work a perpetual assurance

(self-assurance) of the intuition that an image (regarded

as an object externalization of the mental process) is an

essential element of art?

Following the successive stages of the artist-philosopher’s

creation we can observe a characteristic aspect: the

evolution of the image as an element which is subject

to a variety of destructive impacts (distortions being

a result of geometric transformations, multiplications

[repetitions], obscuring and blurring its representation up

to blackout planes used to cover it) and which nevertheless

importunately recurs. Not only in the works on a plane or in

spatial installations, but also during performance actions.

And in the latter the ‘annihilation’ of the image was not

successful. It seems that the artist will probably have to

accept the fact that the image, despite a continuous fight

the relations between the object and its image (drawing,

photocopy), the intruder, which, changing the context of

objects’ functioning, disturbing (or expanding) the process

of perception of the complex relations, makes us consider

their ambiguity.

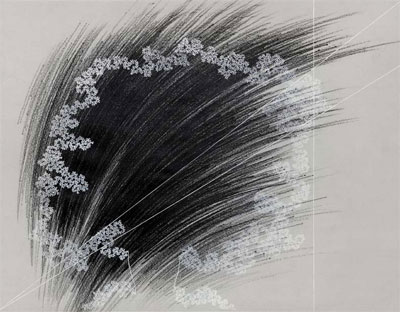

Dwa nieprawdziwe obrazy drzewa VI/3, kredka, olej, papier, 49,3 x 63, 1988

Two False Images of a Tree VI/3, crayon and oil on paper

Dwa nieprawdziwe obrazy drzewa VI/3, kredka, olej, papier, 49,3 x 63, 1988

Two False Images of a Tree VI/3, crayon and oil on paper

The same object is presented many times from different

points of view, which suggests relativity of various

perceptions of reality. Similarly the question of identity

comes into our mind when in one of the works we observe

a set of slats, an object counterpart (in quantity and length)

of lines that make up a given shape. In other doings the

image of a tree first put on the profile of a two-dimensional

figure and then a solid figure is subject to changes being

a result of the impact of the background shapes. When

placed on the spatial material it changed the status of its

existence.

Herein we are concerned with a specific kind of relativism.

Is the picture still the same image? Is it still the image of the

same object if it takes various shapes, depending on the

character of the operation? Thus, is the comprehension of

the notion still the same when we change the context in

which we function?

Acting with tracing paper (to which the motif of a cross or

a triangle is subject), its multiple folds and a simultaneous

transformation of an image which it depicted, increase

an impression of illegibility of the basic meaning of the

element; like clichés too often used in a variety of contexts.

In all stages mentioned above the image was deformed, yet

it still existed; it not only did not disappear but it transferred

into self-quotations, it also became an element of real

space, first by introducing textural elements, and later by

becoming components of the real space of an installation

and then of the time and space of a performance.

Moreover, all these activities simultaneously stressed relativity

of our perception. Considering the artist’s position, they

somehow devalued the conviction concerning the likelihood

of existence of the only true System whose goal was to

present the matter in the way to reveal the essence of what

is spiritual, absolute and universal.

In the early works there was a tree – an emotionally neutral

motive. Then some other motives appeared, burdened with

numerous meanings and possibilities for interpretation

(the cross, the Shield of David). To some extent it might have

been a manifestation of yielding to personal emotions, the

pressure of the external context.

The artist himself stressed the potential presence of a personal,

physical factor – e.g. a sign of exhaustion. Was not the

decision to abandon photography as a medium in the

process of preserving and duplicating an image associated

with a desire to fill a work of art with some emotions

connected with the imperfections of the work done by the

human hand? And does not the very effort of calligraphing

the juxtaposed fragments of the image of a tree mean

a kind of meditation – a specific philosophy of life?

And what about emotions associated with the experience

of everyday social, political, cultural reality? Is not the

use of imagery motives rooted in culture, ambiguously

meaningful, a trace of such emotions? These signs

can obviously be regarded as a set of lines apt for

transformations, however, the effects of transformations

deliberately performed on them, together with their

meaning conveyance do not merely occur as a random

act, they are predictable. Apart from the diagnosis of the

state of the depicted semantic areas in culture (superficial

treatment or Sacrum decline, cultural transformations,

conflict of value systems of the contemporary world) the

artist wanted to say about a sign worn out by the superficial

approach to the sphere it evokes, or the separation of the

sign from its essential designatum.

And is that by chance that the paintings whose basic

imagery motives were shadowed were created in the mid-

1980s? Do not they contain echoes of the events of that

time? The incompleteness of imitating the visual sphere in

these paintings could be a reflection of the incompleteness

of existence.

In his works, with the use of self-quotations, Grzegorz

Sztabiński – through retrospection – referred to the past as

well. It was obviously an attempt to capture the work of

art as a whole, and to find the primary sense. Taking the

character of the image memory into account, the memory

which does not exactly preserve the features of creation

chronology, it was not possible to reach that goal. It seems

however, that the artist was not only motivated by a desire

(or a hope) to keep the logical memory of the whole artistic

process, but also by the emotional purely human desire

to preserve moments from the past, to form them into

a coherent continuous whole.

Turning to nature was a special moment in Grzegorz

Sztabiński’s work. Nature and its deliberate dynamism had

been primary and standard for art for a long time, being in

the past a criterion of assessment of what is well-founded

in artistic endeavours. Art transcends the world of nature

and together with science, morality and religion it creates

the world of culture.

The elements of nature which appear in Grzegorz

Sztabiński’s creation build or participate in creating

installations. They become a more and more important point

of reference, though the number and character of these

elements are limited. What happened in the installations

was a transfer from a two-dimensional image of a tree,

through its presence intensified by texture, up to the physical

existence in the form of twigs. The arrangements of

twigs and slats are considered by the artist to be signs of

a mysterious language which nature uses to talk to us.

The artist emphasised his strong emotions concerning the

mysterious character of nature and the need to read out

the signs of nature to discover the truth hidden there.

The numerous actions mentioned above accentuate

the significance of the emotional factor in Grzegorz

Sztabiński’s work. The art, that, considering its nature,

should be reserved and calculated, dominated by the

philosophical aspect in its concept, and the geometric one

in the image, was in this way really ‘human’.

In the course of the artistic process of verbalising an

abstract idea the artist juxtaposes elements deriving from

a realistic (real) background, such as e.g. images (signs) of

trees, branches – in his installation he uses everyday objects

as well – composing them with abstract, geometric forms.

It was stressed many times that the aesthetic value, the side

effect here, is not the superior goal of this art. Nevertheless

Grzegorz Sztabiński’s works evoke unquestionable

profound visual qualities, they are of great aesthetic value.

Grzegorz Sztabiński’s art is not merely a reflection of

intellectual considerations, but also a material construct

containing some specific visual motives, subject to the

rules of artistic formation of an image. Even the way the

effects of logical operations (diagrams, grids), equivalents

of abstract phenomena are formally presented on a plane,

depends on the author’s will.

The aesthetic values of paintings and drawings as well as

Grzegorz Sztabiński’s spatial compositions are irrefutable.

The artist’s works are dominated by subtle plastic actions.

A drawing of the crown of a tree, made with great precision

– even for that reason that it is necessary to repeat it – creates

a kind of sophisticated ornament. Fragments of the tree

crown also look as perfect images (though they are not),

showing the similarity of a fractal to its part. We take great

pleasure in following the ducts (one- or multi-coloured)

contrasting with the background, which give way to lines

reflecting that element of nature and rhythms that are the

effect of some definite presumptions, according to which

the components of the whole sophisticated composition

are organised.

We feel that its particular parts (planes dominated by

the rhythms of tree contours, those characterised by

distortions as well as ‘the realistic images of a tree against

the background’ or geometric symbols) were arranged

with great care and skill, as far as their size, priority and

mutual proportions were concerned. The artist uses the

plane to juxtapose abstract and organic forms, irregular

dispersed (the tree crown, the lines of frottage…) with

geometric ones.

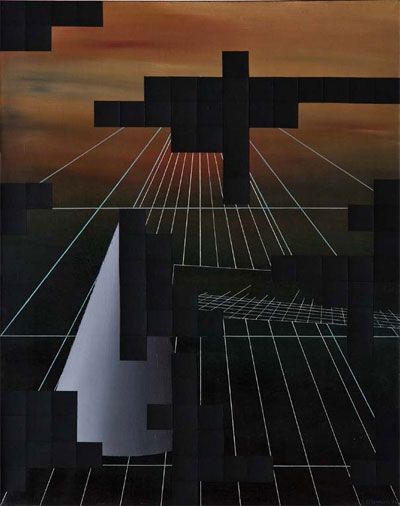

Obraz drzewa, kredka, akryl, olej, płótno, 54 x 65 cm, 1988

Image of a Tree, crayon, acrylic and oil on canvas

Some of Grzegorz Sztabiński’s paintings, though they are

characterised by obvious care and the tranquillity typical

of any complex reflection, are more dynamic. Not only is it

expressed by stronger accents of emotions, but also by the

intention to test some rules with regard to the phenomenon

of movement – such disturbances as dislocations, rotation,

suggesting ‘vanishing’ perspective. This kind of endeavours

can also be considered to foreshadow the advent of the

next stage – going beyond the two-dimensional space

into the area of the installation or performance.

In the artist’s works colour is subordinate to line. Colouring

focuses on a limited palette. It comprises perfectly sensed

reds, metaphysical blues, greens and browns juxtaposed

with black in Sposoby bycia (Manners of Being),

phenomenal, tonally distinguished colours in Pamięć

obrazu (Memory of the Painting), palettes of greens and

blues in Milcz±ce collage’e (The Silent Collages), a variety

of ‘dimmed’ browns and greys in Między-rzeczy (Inter-

Objects) or Cięcia (Cuttings).

What is striking here are the attempts to expand the

paintings’ space obtained by juxtaposition of coloured

and black planes, by placing fragments of the composition

in shadow, half shadow and light, when the shadow falls

widely on the plane of the painting owing to the use of

different kinds of perspective; in the installation the space

of the exposition, naturally deep as it was expanded by

means of the elements lying on the floor and those hanging

on the walls, is even additionally deepened by the perspective

exposition of the drawn objects.

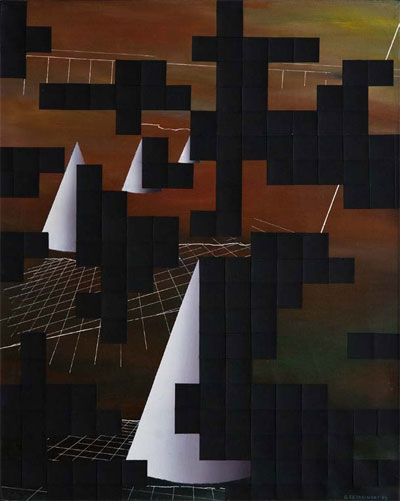

Milcz±cy collage VIII, olej, papier, płótno, 81 x 65 cm, 1988-2004

The Silent Collage VIII, oil and paper on canvas

Milcz±cy collage IX, olej, papier, płótno, 81 x 65 cm, 1988-2004

The Silent Collage IX, oil and paper on canvas

The paintings, in their spatial character created by multilayered

representations, obtained by mutual contrast of the

representational and abstract elements, simultaneously

depicted making their way to the Absolute, the Rule, the

Whole by penetrating the spheres of the unknown. In

three-dimensional works this antinomy occurs as well:

the recognizable objects and their images are followed by

traces of geometric actions performed on these objects.

These endeavours – apart from being representations

of relativity in identification of an object and its

representations – are also an attempt to recognize varied

spaces where respectively: the object, its visual image

and the reflection concerning their mutual relationships

function. It also reveals, in a metaphorical way, the

development of a concept, its recedence, sometimes its

deconstruction and deterioration (moving away to the

shadow sphere).

Some researchers state that, when considering Grzegorz

Sztabiński’s works, the viewer is able to notice mainly,

or merely the aesthetic values of a work of art (colour

arrangements, shade and light effects, the rhythm of the

elements, perceptible lines of tension), however, it is possible

to conclude that the means of expression properly selected

by the artist undoubtedly draw our attention to the very

essence of the operation. Inquisitiveness of viewers who,

for the last few decades, have been used to Neo-Avantgarde

art, as well as their increased cultural competence

are the reason why they are able to understand at least

a part, an outline of the game which Grzegorz Sztabiński

plays in the realm of art.

As beholders we first of all succumb to the feeling that

we face a work of art that is genuine, reliable and honest.

It happens that even if we do not know the rules that

determine a given artistic message we take great pleasure

in having contact with it. Grzegorz Sztabiński’s work is

a case in point.

The search within the universal values and their

relationships, because of its logic and order, evokes

a specific sense of… beauty. As beauty can be discovered

in many ways: it is the beauty of what is presented, the

beauty of the way it is made, the beauty of an artistic

concept with its consistency as well as the real beauty

when a work of art truly enriches man and the world.

In the kind of art intended to be a mirror reflection of reality,

the relations, connections and proportions which have

an impact on the composition and appearance of the

elements seem to give us certainty, they create an illusion

of the world’s cognition. In common perception they are

a source and a guarantee of beauty.

Although Grzegorz Sztabiński does not resign from the

tangible character of art, the aesthetic factor appears to

be of secondary significance. What is essential here are the

rules controlling the composition of the elements, inspired

by mathematical, logical laws or created by the artist, not

a reflection of the visible world based on the observation

of reality. The fundamental oppositions were illustrated

by the artist by means of the similar imagery motives.

However, he used his own varied rules, depending on what

abstract notions he had in mind.

The sense of purposeful and consistent actions (their

precision and accuracy as well) is very clear in these works.

And even when the artist, accepting a mistake (which is an

effect of the search), changes the algorithm – we trust him;

there is a sense of harmony based on the conviction that

the means of expression and the assumed goal have been

properly selected. The difficulty in perceiving the whole of

the phenomena (due to a physical inability to continue

the reflection which is a result of the immanent infinity of

the process or the constant decrease and the final atrophy

of the visual elements) might be a source of subsequent

logical decisions – their tangible sense brings the viewer’s

satisfaction.

In his work Grzegorz Sztabiński tries to convince us that by

means of visual forms we are capable of perceiving only

a part of the phenomenon of existence. The attempt to

make all the processes that take place in it visible is typical

of human beings, yet as the artist’s search proves it is

condemned to failure.

In the artist and philosopher’s endeavours there is an effort

to comprehend and capture the Divine Logic. The creator,

who can not achieve it only with the tools of philosophy,

aspired to do it with the means of artistic expression.

He realises the common desire for cognition, trying to

discover, to understand and to abolish the fundamental

oppositions. Coming across some obstacles on his way, he

absorbs the successive experiences, taking a challenge to

the man, the researcher and the artist.

His creation is due to neither incomprehension nor

certainty and understanding – it is an expression of search,

a desire to reach the truth, despite the fact that at the

moment of failure it would be easy to continue an act of

unreasonable defiance, resigning from all kind of reflection

– as he claimed in his writings.

In the logical sequence of search Grzegorz Sztabiński does

not ultimately offer us the image of what is absolute. The

speculated logic of operations sustains a failure against

the imperfection of reflecting the visual factors. However,

the works are an expression of the world’s improvement

and the natural nostalgia for the ultimate perfection.

Grzegorz Sztabiński’s evolving art is an expression of

transience, a process of changes involved in eternity. The

artist shares a sequence of actions with us, the actions that

are a representation of a given process.

Grzegorz Sztabiński’s attitude is a great pilgrimage

through the area of art and philosophical reflection. The

artist not only wishes to exist in the world but to be there as

a reasonable and creative being

Dariusz Le¶nikowski

Transl. Elżbieta Rodzeń-Le¶nikowska

Covering, shifting, disappearing

Shifting, covering and removing are frequently employed in

the course of artistic activities. Shifting an element, say, by

moving it from the center of an arrangement to its margin,

it is a procedure which aims to improve the composition or

change its character (e.g. to convert it from open to closed).

Covering, also known as „masking” consists in covering

a certain shape in order to check what the arrangement

of other components would look like should it be omitted.

Disappearance is realized by partial or complete removal

of some form. Typically, these procedures are treated as

purely technical, useful during certain stages of completing

the final version of the work. An artist forgets about them

as soon as he finishes his work. The viewer usually does not

realize whether and which elements of the composition

were subject to the processes described above.

I realized the potential in exposing such actions which,

during normal painterly work or drawing, are treated

as purely pragmatic while I was working on my series

Silent collages/ Milcz±ce collages. The starting point of

these realizations were my oil and acrylic paintings I had

completed in the eighties. Several of them were showcased

at exhibitions, a few were sold, but in general this cycle

failed to give me a sense of satisfaction. In 2004, I used

these paintings in an action which can be described as

„masking” of a kind. I covered places which I found especially

irritating with small squares cut from white or black paper.

The effect encouraged to reflect on its meaning, so I pasted

paper elements on the previously painted canvas. Thus,

I fixed the result of the action of ‚masking’, which in the normal

procedure of painting is removed in the final version of the work.

Thus, paintings became dual in nature. They were connected by

two periods of time, two decisions that were taken.

Pasting pieces of paper onto paintings is associated with

collage. For cubists, dadaists, surrealists and constructivists

this technique was a new way to create works of art. Its

advantage was the possibility of creating a link between

the work and the daily life through a direct transfer of its

parts onto the painting. Collages were thus „eloquent” – in

cubism, they made the meaning of drawn or painted works

concrete, in constructivism, they were the confirmation

of the materialistic nature of the surface and actions

performed on it, in surrealism, they constituted a smooth

transition towards the surreal.

Therefore, the pasted

fragments had to have a distinct character, to be rich in

meaning. In the case of my actions, this situation was

changing. Black squares of paper smothered the earlier

painterly expression. They introduced areas of „silence”.

They questioned the conclusion of the painting process,

expressing doubts about the validity of the solutions

used during it and also provided evidence of the arbitrary

character of considering any result of work as final.

The idea of the painting underwent destabilization, as the

possibility of reenacting the process of transformation was

thus revealed.

I asked myself, therefore, a question whether such a peculiar

performativization could not have appeared previously, in

other forms, in my artistic actions? Reflecting on this issue,

I drew attention to shifting and disappearance occurring

in the painting and drawing cycles I had been producing

for over forty years. They consisted generally of a few

or a dozen works, which differed in that some of their

components were subject to shifts in subsequent projects.

This process occurred in a systematic way. The overall

distribution of elements on the plane remained the same in

the subsequent works comprising the cycle. Only selected

shapes changed their position, gradually being shifted

up or down, to the right or left. Sometimes, the process

of shifting took place in relation to one shape, such as

an outline of a tree.

In subsequent drawings or paintings,

I showed its parts in various configurations (e.g. 1/6, 2/6,

3/6, 4/6, 5/6) in order to eventually provide a complete

shape. Sometimes, I also used a reverse principle, moving

systematically from an entire shape to its parts, and then

disappearance. Later, from the early eighties, I linked this

kind of transformative approach with the change of the

form I used. I still used the shape of a tree but I also used

an outline of an equilateral cross, star, triangle or a specific

letter. I drew a given form of tracing paper, and then I folded

the paper, which led to unexpected transformations

of the initial theme. Drawings on tracing paper I either

included into my work, or moved the resulting deformed

shapes onto the surface of paper or canvas. This resulted

in destabilization of the patterns of familiar forms. They

were simultaneously associated with what we know,

while going beyond the dichotomous oppositions which

we use in everyday life and which we also employ in art.

What followed was a dynamic oscillation between the

initial shape and the directly observed modified forms.

Sometimes, I placed such an initial shape in the work

treating it as a reference point, at other times I let the

mutated elements to function independently.

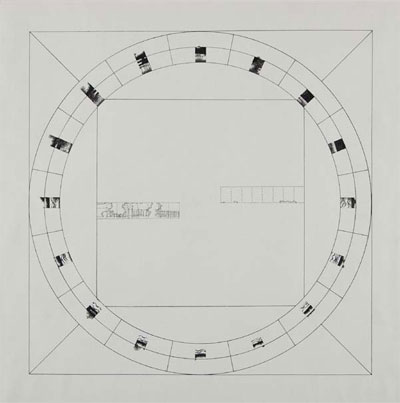

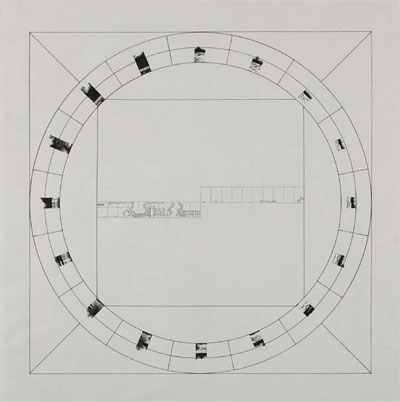

Między skończono¶ci± i nieskończono¶ci± II, tusz, papier, 50 x 50 cm, 1979

Between the Finite and the Infinite II, India ink on paper

Między skończono¶ci± i nieskończono¶ci± V, tusz, papier, 50 x 50 cm,1979

Between the Finite and the Infinite V, India ink on paper

Operations described were always conducted

systematically. The basis of the activities were numerical

sequences, in various ways related to the principles of

transforming the elements. The reason for adopting an

objective basis of the activities („the rules of operation” as

I described it in the title of a series of paintings in 1975) was

to provoke a kind of randomness. I was not attracted by

purely subjective decisions related to the transient emotions

or a free movement of the hand. The unpredictable (and

in this sense, random) nature of the shape undergoing

transformations was to be a result of the application of

the adopted algorithm, and thus in some sense forced

by its relevant characteristics. The element of emotion in

my work was connected with the expectation of what the

result would be of strict adherence to predetermined rules.

Disappearance of elements in the cycles of paintings

or drawings was also a consequence of assumed

transformations or shifts. Steadily moved elements came

to a certain limit (it could be a drawn shape or edge of the

plane) and this situation, to continue their movement in

subsequent work from the same cycle became impossible.

Also, the changes in the shapes were to suggest the

existence of other possibilities of transformation which

I did not include. Therefore, in my comments to these

projects I often suggested that the movement according

to the rules can continue, but outside the area of visibility.

I also encouraged the viewers to continue the activities

which they learned watching the presented works, and

to imagine the infinite development of transformations

suggested in them.

The quest for intellectual stimulation of the audience,

getting them to treat works is not as definitive, optimal visual

solutions, but as a stage of performative transformation,

accompanies most of my artistic activities. In the early

eighties, these suggestions led to singular actions that

can be categorized as performance art. They consisted in

a public presentation of the transformation process which

I applied to the elements that appear on paper or canvas.

I showed the most extensive action of this kind, entitled

Poza obraz (Beyond Painting) for the first time during

the Third International Symposium of Performance Art

in Lyon in 1981. It sparked interest because, in addition to

actions, the performers were then to present their visual art

works. Art critics present at the event emphasized the close

relationship between artistic creativity and the shown

action in the case of my artistic output.

As a consequence of the so-called performative turn in

contemporary art, as well as in theoretical considerations,

emphasis is usually placed on questioning the boundaries

between artistic disciplines. In various areas of art, one

attempts something that resembles a spectacle.

I think

that this also applies to the activities of some artists using

traditional means of art. Then, their thinking and actions

do not culminate in a single work. This is not a realization,

where, by developing the concept, the preparatory phase

and, finally, the execution one aims at a single object

which is the sum of experiences and thoughts. Specific

works are rather stages on the road – illustrating the

state of reflection which will progress further.

8, 9. Poza obraz, performance, 1981 / Beyond the Picture, performance

Therefore, it

is not contemplation that is expected of the recipient but

interaction. Sometimes, it is physical in nature and consists

in interactive participation in the shaping of an object

or situation. This activity, however, can also be mental in

nature and rely on taking into account factors related to

the development of something, the occurrence of shifts,

noticing covering or unveiling, realizing the disappearance,

which consists only in going beyond the area of visibility,

or sometimes a complete annihilation.

KATALOG

KATALOG

|

|

|

|