|

|

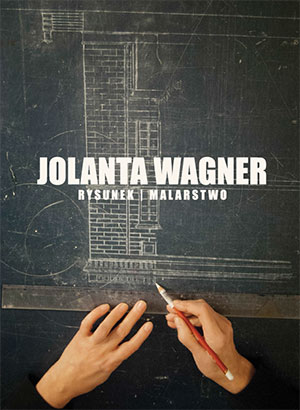

Jolanta Wagner »

MALARSTWO / RYSUNEK

Ad Infinitum

In his essay The Infinity of Lists Umberto Eco wrote that the

abundance of technical means the modern man has at his

disposal, and the excess of wealth he produces actually

weaken and degrade him1. The constantly growing number

of things make us continually gather and describe them.

Thus, modern civilization is characterized, among other

things, by the overwhelming excess and the sense of

chaos. The response of the lost and irritated man is either

the willingness to abandon the topographical and cultural

space that surrounds him or the pursuit of order. The

latter attitude is also a kind of opposition to the currently

dominating model of the world.

It is obvious that restoring order can only concern

a fraction of reality; nothing more can be reached due to

the pace of the ongoing changes and the degree of the

increasing specialization and concretization.

Jolanta Wagner organizes the world for her private use. Every

time she creates her works, he tries to control a fragment of

a particular universe. The awareness of mastering a piece of

paper, a small territory whose sovereign she becomes, gives

rise to the sense of regaining the lost peace.

Thousands of years ago, in the early days of art, trying

to overcome the sense of the horror of existence and

misunderstanding of the world, the man drew images on

sand referring to the surrounding reality. It was an attempt

to understand and control the nature and a way to find

a reassuring order.

Jolanta Wagner’s collection of works is like the world in

a miniature, a representation of the Unity. Works are not

obviously examples of ordinary inventories of things. Even

if they imply that they are governed by the imperative of

practicality, they are primarily poetic, metaphorical.

When we look at her works, sometimes we get an impression

that the artist pursues the strategy of conceptual art. An

important feature of this art, however, was the rejection

of aestheticism. The visualization of the work was only a

means that helped read out its essence. Additional texts,

sketches or plans had only an explanatory function, helping

to visualize, materialize thoughts. The apparent logic and

rationality of the works were a kind of mystification; they

were merely a method to mask the proper work of the artist,

which was realized as a thought process. The artists’ search

led to the impersonalisation of the language of art2.

In Jolanta Wagner’s view the aesthetic aspect is

nevertheless essential. The form is significant not only

as a vehicle for the documentary content. The shape

of the poetic message derives from the development

troof

calligraphy.

Signs are somewhat ‘magical’ in their

nature. Activities and texts, working like charms, as in the

alchemist’s studio, support the creative process.

It is more than coincidence that the artist uses worn sheets

of tracing paper originating from some architectural studios

as a background for her drawings. They have a special

value. The technical drawings included there represent

many qualities important to the artist. They represent and

document. They are precise, quasi calligraphic – they are

beautiful in a way. They are also a special testimony of the

past (though the artist herself heads for the future, trying

to think ‘forward’). They are traces of someone’s actions,

struggles, emotions. Drawing on the worn worksheets,

the artist broadens the world, and the pre-drawn pictures

are its fragments. She adds to these pictures a fragment of

today’s reality, enriches them with new motifs, personal

experiences and feelings. Perhaps it is easier when it

happens on the old, already used tracing paper because

it seems to be a ‘rough version’, and one is more likely to

overcome the ‘fear of a blank sheet of paper’.

Both records come together in a special symbiosis. The

artist performs various, once minor, once more complete

interventions in previous drawings. As a result, they blend

more completely with each other, the context becomes

wider, the visual aspect is more complex. The most

extreme example of such activities is the use of the original

drawings created earlier by the artist as a background for

the successive vision. One of the plans of the city spread

out on the surface of paper with its houses, towers and

walls on a barely visible outline of the previous map. In this

way it obtained its original, largely imagined story.

The tracing paper used by the author is mostly old and

damaged. The yellow sheets resemble the materials from the

past, such as parchment or papyrus. They tell a story. Their poor

condition adds to their antique nature and it gives credence

to the passage of time. The artist does not care about flaws,

such as smudges or tears. The defects are corrected and they

become the elements of a constantly developing story.

Jolanta Wagner also uses new sheets of tracing paper.

In this case, it poses a different challenge to the artist. The

blank sheet becomes an unknown land to her, an area of

a peculiar clean, ‘unwritten’ board.

The very concept of tracing paper reminds us of the motif

of retaining, but also copying something. The collection of

works is like a self-reproducing, constantly supplemented

and quoted message.

That motif is most strongly connoted by technical tracing

papers used to make copies on drawing boards, which

were adopted by the artist. The boards themselves also

become the space of artistic exploration. They have a

specific quality: various defects, protrusions cause that the

drawing looks slightly different. The ink reacts differently

to the original background, the lines are more diffuse –

4

the drawing merges into the drawing board, its structure

absorbs the recorded story.

Jolanta Wagner also creates her drawing works in chalk on

the blackboard, like in a kind of ephemeral land art, being

ready for the risk of rapid changes and transience, the

possibility of the vision disappearance. When we take into

account the earlier contexts (for example, what happens

with old technical drawings and the fragile material the

artist uses in her artwork), such activities seem to be

relevant and coherent.

The visions of the city are a significant visual motif of a large

part of Jolanta Wagner’s oeuvre. Old urban maps were the

inspiration for creating many of them. The images of cities

drawn by the artist are half real, half fantastic. In some

cases – it refers for example to the maps of ŁódĽ (including

Plac Wolno¶ci drawn on canvas, buildings in Piotrkowska

Street, the house where Władysław Strzemiński lived),

Czech, German and Italian cities – we are able to recognize

even specific buildings and their familiar details.

It seems,

however, that the correspondence of the created vision

to the actual shape of the objects is not the main goal

of the author. She rather creates a kind of universal, but

varied architecture with archetypal, model outlines of

houses, castles and bridges. At times, even the motif of the

‘impossible’ architecture appears, though it is not drawn as

accurately as, for example, by Maurits Cornelis Escher.

In his book Invisible Cities Italo Calvino evokes the motif of an

atlas that ‘also shows the cities about which (...) geographers

do not know if and where they exist but they could not be

missing among the forms of possible cities. (...).’3

Jolanta Wagner’s cities are built centrifugally, the houses,

sometimes increasingly sparse, like in Map of the Town A.,

stretch radially towards the outskirts, at the same time to

the edges of the work of art, creating an impression of

immeasurable continuity beyond its frame. Running out

of the drawing, the streets connect somewhere in space

with others that cross the boundaries of the next picture.

There, in the second picture, single houses and roads run

– converging towards a central building or square. Eco

emphasises that in the case of that structure cities have

their centre, because their suburbs connect with each

other outside the image – the world they represent is

deprived of it, its structure is not centralized4. It is like in

the postmodern vision of the world, where there is no

dominant centre that organises the entire structure. And

like in the concept of rhizome by Gilles Deleuze and Felix

Gauttari, which refers to the non-hierarchical model of

reality controlled by a network of specific connections

– relations occurring between the world of nature and

culture or their elements5.

On various levels Jolanta Wagner’s attitude combines both

rationalism, the need for order and idealism supported by

a certain kind of innocence. It does not come as a surprise

that one of the artist’s favourite painters is Cy Twombly. His

artwork represents a desire to escape from rigid conventions,

expressing longing for sincerity and spontaneity.

The maps drawn by the author are characterised by

a specific perspective – a topographical image typical of

naive, children’s art, or of historical conventions in which

the idealist element was dominant over the modern

realism. The maps of the world, typical of antiquity and

the Middle Ages, have a special position here. The fact of

belonging to a certain aesthetic formation is reinforced

by numerous additional images characteristic of Western

European panel paintings or compositions that form

kleimo, the borderline surrounding the iconic Byzantine

paintings. Moreover, these works are also characterized by

lively unrestrained colour scheme.

Such works in Jolanta Wagner’s artwork are not only

the expression of longing for sincerity of the means of

expression, but also an attempt to introduce a tinge of

mysticism, nostalgia for something distant – in time and

space, for something intangible and elusive. Also for the

arduous creation which posed a challenge for a cloister

scribe centuries ago.

References to calligraphy are visible in the artist’s work

on many levels. The works previously discussed originate

from such an attitude. In the case of colourful maps and

Calendar, calligraphic associations are also noticed on

the level of the material background which is a thick,

handmade paper with its organic and archaic nature.

This sphere of creativity also connotes a number of

oppositions typical of Jolanta Wagner’s entire work, such

as the opposites: poor – rich, simple – sophisticated,

sublime naive, elite – common, mass-produced – unique.

In his work titled Venus of the Rags (1967, 1974),

Michelangelo Pistoletto, one of the Italian representatives

of arte povera used the statue of the Roman goddess

looking at the heap of rags from a second-hand shop,

thus confronting the unique classic symbol of beauty with

products of today’s world of mass overproduction.

Jolanta Wagner juxtaposes mass-produced objects, such

as for examples packages of luxurious perfumes, creating

not only drawing visions, but also spatial compositions.

She combines the desire to use ‘fabulous things’ with

the idea of documentation. The installations are part

of a general inventory of items. They are here because of

their attributes (including the scent that releases not only

the aromas of perfume ingredients, but also an aura of

exclusiveness and prosperity) and because they reflect the

echoes of someone’s presence, combine the vicissitudes of

the original owners with the objects’ further story, to which

the artist contributed herself with her creative activities.

In these works Jolanta Wagner provides another kind

of documentation, not deriving from the pure ‘infinity

of the lists’. Nor is it just a message commenting on the

condition of our culture of excess. Piles of objects – even

that composed of books – although they come mainly

from the present, they become guardians of memory; the

message is a kind of memento. The compositions evoke

the echoes of the holocaust in Auschwitz. That motif

was also present earlier in the ‘technical’ drawings of the

Radegast station.

The nature of Jolanta Wagner’s creation is associated with

the idea of new realism. It brings to our mind the works by

Arman, Daniel Spoerrie, where artists use ordinary objects,

everyday things, ‘poor’, ‘low rank’ goods. Such things just

wait to be artistically ennobled. The fact that they have

been selected and exposed turns them into art, though

some of them have already gained the status of being

‘beautiful’ (for example, a sophisticated, albeit slightly

worn cup). Beautiful items – even damaged – still remain

beautiful. It was the designer who gave them that value.

However, when the artist uses them in the composition,

they are taken to another, higher level. The ‘added value’ of

many objects also lies in their individual stories, the secrets

they hide (Inventory of a Wardrobe).

In a series of works titled Poubelles (Garbage) Arman

accumulated objects and embedded them in the

material. Jolanta Wagner covers her tracing papers with

wax. The wax is not just a security measure. It ‘warms

up’ the images which are underneath. The background

changes its character – it feels different. The encaustic

painting is an ancient painting technique. Images painted

with wax paints were durable, and colours were brighter

and deeper. That is why the Fayum portraits are still so

impressive today. Wax became a kind of reminder, like in

the works of the artist from ŁódĽ.

General Census which the artist carries out will never be

completed. It is obvious that we are not able to archive

everything. Someone who undertakes a similar task is

accompanied by a subjective feeling that it defeats them.

In terms of aesthetics this feeling is defined as infinity.

And Italo Calvino wrote: ‘The catalogue of forms is endless:

until every shape has found its city, new cities will continue

to be born. (…) In the last pages of the atlas there is an

outpouring of networks without beginning or end…’6

Dariusz Le¶nikowski

Transl. Elżbieta Rodzeń-Le¶nikowska

KATALOG

KATALOG

|

|

|

|