|

|

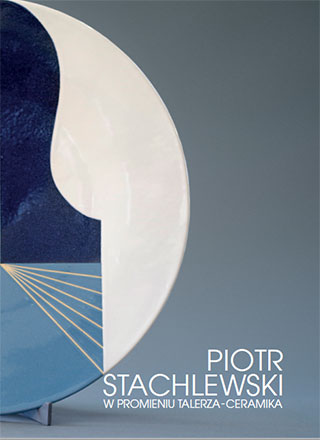

Piotr Stachlewski »

W PROMIENIU TALERZA - CERAMIKA

On the occasion of the exhibition of

Piotr Stachlewski’s ceramics at the Amcor Gallery,

Dariusz Le¶nikowski talks to the Author.

Dariusz Le¶nikowski: You are an artist practising various disciplines. You create paintings, you draw, deal with

printmaking. For years you have exposed the Logoman motif in your works. What made you turn to ceramics as well?

Was it the desire to seek more inspiration and opportunities for the artist?

Piotr Stachlewski: A dozen or so years ago, we used to travel with our children around Poland during the May weekends to

see something, to visit some places. In 2010, we decided to go to the Archaeological Reserve in Krzemionki Opatowskie and

Krzyżtopór Castle. On the way we saw an advertisement inviting visitors to the Porcelain Museum in Ćmielów. Since we had

time, we decided to go there. The museum was new and impressed me a lot. In the showroom there were numerous projects

designed still in the communist era during the New Look period by the most prominent designers of the time.

I began to read about ceramics, including manuals for beginners. Slowly the idea of a plate began to crystallize, which is a good

space for expressive drawing originating from my graphics. I felt that it could free me from the tedious work of printmaking and

expand the space for this form. The Logoman motif was thus to make a transfer into the realm of design. It seemed to me that

it would not be difficult and I would quickly be able to grasp the technical side of producing a plate. I didn’t know how wrong I was...

I asked friends about ceramic studios in the city that have the technical capacity to fire in the temperature range suitable for

porcelain. It turned out that it was possible, but very expensive. Then I made a decision that it would not be porcelain, but

stoneware.

DL: What captivated you in ceramics? Was it the need to face something more “artisanal”, concrete and at the same

time technological? After all, it is sourcing the material, forming the object by hand, firing, skilful use of pigments...

PS: For many years, despite the current possibilities, in painting I have not given up making the stretcher myself, fastening the

linen canvas, applying glue and priming on my own. Minor departures from the norm happen to me as I get older. Indeed, I like

this craftsmanship aspect, as you called it. In ceramics it is obvious. When I started my adventure with ceramics, I had to show

some ingenuity. Solving problems is frustrating on the one hand, but on the other it makes you euphoric when you know that

you have solved it and that your solution is repeatable. I remember that at an early stage I chose the technique of making a plate

using the impression method in a plaster mould. But where to find one? I searched for the right shape at scrap yards, then at

the IKEA store, and found it at the Academy - in the painting studio, next door. It served as a prop - a round, slightly spherically

convex Plexiglas mould. The ideal. Up to this day I haven’t figured out where it came from and what it was originally used for,

but for me it is an extremely valuable object, a matrix necessary for casting a plaster mould. I also have my technological secrets

worked out during the many stages of plate production.

DL: Don’t you think there is something atavistic in this work, something that accounted for one of the earliest and

most important achievements of mankind – the ability to form and fire dishes. An attempt to return to the past and to

something primal...

PS: I believe that ceramics is a close cousin of culture. A short and beautiful essay on pottery was included in the book

The Meaning of Art by Herbert Read. In a few sentences he described the history of this craft and emphasized its significance.

He wrote that it is a fundamental art, connected with the elementary needs of civilization. I was very impressed by the books

Porcelain Through the Ages (George Savage) and The White Road (Edmund de Waal), but even without reading them I know that

ceramics is an important cultural field. I would only add that it is more appreciated in England than in our country. While reading

these books, I felt an almost metaphysical connection with all the potters and ceramists working before me. I could feel it even

more when a coincidence or the right decision raised my technical and artistic awareness.

As part of my self-education, I watch other ceramists on YouTube. In search of inspiration, I buy books and albums on ceramics,

monographs of the areas of India, Indochina, Turkey, where the technique seems to be similar to that of distant eras and where

vases, containers and pots the size of a small bathroom are fired. What is captivating about the work of these people, potters

working creatively in remote corners of the globe, is the simplicity and vast experience, turning into almost faultless repeatability.

This aspect of the work was important to me, and still is. My goal has been to get my technique to the point where the plate can

withstand several firings at high temperatures (1075 Celsius), which opens unlimited possibilities for me in terms of its painting

and provides a relatively high degree of control over what is created.

The reference to the past you mentioned does not “turn me on”. I could fire in a kiln prepared in an earth pit or at least in a woodburning

stove. I live in the countryside and would have no problem with that. I can also do masonry. However, I consciously

work with a modern electric kiln, where the so-called firing curve is controlled by a thermocomputer. I mix the clay for joining

the foot of the plate, the so-called mud, with an electric blender. I also do not search through the fields and ravines for clay from

my region, seeing some aspect of ecology or connection with nature. I buy ceramic mass from a well-known German company,

which, like most ceramic materials, is delivered to me by a courier.

DL: You make various ceramic objects. Some probably more for pleasure, for experimentation. It goes without saying

that the recognizable object for your ceramic artwork is the plate. For you, is the form of the tondo a constraint you

have to deal with, or an aspect you have consciously chosen to discipline yourself?

What are the consequences of choosing such a form?

PS: The procedure I have tried and tested for making a plate requires that I use unaerated ceramic mass to work on it. After the

plate is formed, however, some clay remains, which is used to create a series of vases for the wife, screens, idols, which function on

the margins of my ceramic work. I also use the leftovers to prepare plates for colour samples. I need about a hundred of them

each year.

As I’ve mentioned before, from the outset I have been interested in ceramics because of the plate and the possibilities of painting

in the circle resulting from its shape, as a provocative variation. But three years passed from the first attempts in the spring of

2011 to the moment when I developed the current form of the plate. Simultaneously, I created projects - sketches and drawings.

During this period I managed to make only a few objects that had a painting layer. Thus, a large collection of unrealized projects

developed, referring to the linear rendition from graphics. Around 2013, a distinct trend began to emerge that took into account

my experience of working with glazes and engobes. I included the plates from this period in the series Celestial Bodies.

DL: You titled one of your series of works Ockham’s Razor. This motif is related to the postulate of economy of thought.

Transferring it to the area of your artistic work, is it a kind of postulate directed to yourself to get rid of what is excess

and what forces you to look for the simplest solutions to achieve an artistic effect?

PS: The title is often born in the course of work. This was also the case here. Ockham’s Razor is close to the postulate of simplicity

and constraint. A phrase “entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity” comes to mind. The colour scheme is limited here, the

compositional discipline is perceptible. Admittedly, it is possible to imagine even simpler structures, completely minimalist and

perhaps fulfilling in a more rigorous way the postulate contained in the title. Most of the projects in this series depict Logoman

fragments and stains of colour defined by radiating lines. However, the title also oscillates around other associations: the forms of

these plates literally have something of razors, knives, cleavers, bringing to mind the utensils of a barber or surgeon. The purpose

of these cool forms resists explicitness. The word razor in this context slightly disturbs the balance in our imagination.

DL: Oliver Byrne and his spectacular graphic solutions relating to the Elements of Euclid... When we look at his persona

and his achievements through the prism of the beautiful series of works you created, one gets the impression that the

experience was important to you. Was it even a kind of fascination? Can you explain it? What attracts you so much in

this phenomenon? Is Byrne merely an intermediary, directing your attention toward De Stijl or Bauhaus art? Are such

references some kind of clue for the proper reception of your art?

PS: My wife once received as a gift an album entitled Books That Changed the World1. On one of the pages it included a small

reproduction of Euclid’s work Elements, Byrne’s 1847 edition. I couldn’t believe what I was actually looking at. My emotions made

me immediately have a look on the Internet. It turned out that the Taschen publishing house had published a reprint of this book

and it was available on eBay. Two weeks later I had this edition with the critical text in my hands and decided to design plates,

inspired by the solutions in this book.

Byrne’s idea to explain Euclid’s definitions through colour graphics was innovative, and at the same time anticipated the visual

assumptions of De Stijl’s creators. I wonder if Piet Mondrian or Theo Van Doesburg were familiar with this book? Neoplasticism was

close to my heart at times. Some time ago I became interested in Bart van der Leck, who transferred the ideas of De Stijl to ceramics,

although he was also somewhat figurative. Byrne’s extremely inspiring typographic solutions are close to De Stijl, but looking

through this book one senses the energy coming from its scientific potential. This is Euclid, after all! Definitions are there, proofs,

aesthetics is subordinated to didactics and plays a key role. It speaks with the truth that electrifies and stirs the imagination.

What I wanted to take from Byrne was the dotted line. It is something new. And, of course, the colours - yellow and red with

a specific warming hue, perhaps altered by time. By the way, colours in ceramics have interesting names and often refer to our

knowledge of the world or have some poetic overtones. The yellow in Byrne’s book conveys the glaze, which in ceramics has

the trade name corn grain, and the colour of the ceramic background of my plates is almost identical to the colour of yellowed

paper, which seemed to me an encouraging coincidence. I wouldn’t be myself if I didn’t use my, as you once wrote, overform in

these compositions. I try to visually subordinate it to Euclid’s geometry, sometimes leaving it as an unglazed shape. Present, but

unobtrusive. I admit that it got a lot from geometry, and it has the right to use it.

DL: When you previously practised easel painting, and painted ceramics is, after all, also painting, it must be tempting

to use already tried and tested solutions, for example, in the composition of colours or the arrangement of forms?

Or perhaps from the beginning of your encounter with ceramics you tried to find other means of artistic expression,

appropriate for the new medium?

PS: Ceramics is governed by its own rules. Trying to avoid failure, I paint the future project with acrylic on paper in 1 to 1 scale.

Many issues are then already settled. However, not completely, because there are glazes that flow during firing, some fuse in

a painterly way, sometimes forming an additional line at the junction. Sometimes they discolour a section of an adjacent stain

or lose intensity with subsequent firings. Not everyone knows that the colour of the glaze at the time of its application is far

from the one we will see after more than thirty hours, after removing the object from the kiln. With time, you know more, but

each new glaze in the palette of colours used raises many times the possibility of surprise. Sometimes nice, other times... Some

painters or critics like to talk about alchemy in the context of how colour works in easel painting. I invite you to the ceramic

studio, where it is no longer a mere metaphor. The kiln is a chemical reactor! For me, thinking about colour in ceramics has

more to do with printmaking (colour graphics) than with painting. I think having matrices in mind. Thanks to the fact that my

plates can withstand 4-5 firings at high temperatures, I am able to do more. I also have more tolerance, accept chance, and learn

patience, because once the kiln is closed and the firing starts, it’s better to forget everything you’ve just done.

DL: Quotations are an attempt to transfer Logoman’s concept into reality, but not contemporary, but historical, taken

as a sequence of human experiences. What determined the choice of specific motifs?

PS: Basically, the decision was made by chance, sometimes due to the quality of the reproduction. This whole series is a kind of

homage paid to ceramists and painters who decorated ceramic products. There was also a bit of uncertainty in it: can I do it too?

At the same time thinking: how did he do it? I also bought some plates at the flea market and copied the motif from the original.

This was the case, for example, with Old Willow or Worcester Dragon. The composition here is where Logoman’s form confronts

the history of ceramics. It may sound pretentious, but I want it to feel good there. To summarize: I quote what I like.

DL: Skate - are you satisfied with these images? Logoman is rather the epitome of something universal, a kind of

morality play motif. And here, next to it - something very concrete, contemporary, one may say: pop culture.

PS: This series is a kind of pictorial dictionary, in which an image, as you said, a concrete one is juxtaposed with a Logoman sign in

an arrangement corresponding to that image. In this series, I used my own photographs taken at D±browski Square in Lodz, but

I also have a work in which I used Jeff Widener’s photo Tank Man taken on Cháng’an Jiez Boulevard in Beijing (1989) or a wellknown

photo showing a group of Warsaw Jews being led out of the burning Ghetto.

DL: Now a question that seems incongruous: Is it necessary to learn ceramics? What in particular? And how long did

you learn the ropes?

PS: I treat the first four years, when I used the kiln at Twórcze Ego studio run by Agata B±cela, as a learning time. The studio, where

several people create, is the right place for posing questions, looking for solutions. The atelier also had an environmental purpose

- it held classes for children and young people, sometimes adults were also visitors. Besides, normal production went on. In such

a place one uses the failures and successes of others, gains the necessary information. I remember that my appearance caused a little

consternation, because Karolina Gołczyk, who had just graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts and knew me from the school,

was working there. The instructors, however, did not have to teach me from scratch. As I mentioned, I was after some reading of

beginner’s manuals. The first platters and vases were successful, and it wasn’t long before I started experimenting with moletage,

also actively modeling the surface of the dishes. Problems began when the plate appeared, it was a steep learning curve from the

beginning. Now I know that in this studio my problems were unsolvable. I had to have my own kiln to overcome the difficulties

I encountered. Finally, I will say a truism: we learn all our lives. Last year, my plate foot modeling shaper broke. So I took another,

more softly profiled one and worked out the edge with it. I thought everything was fine. A week passed and it was time to remove

the dry plates from the mould. The only area I could get hold of the plate so far was the foot. This one - too softly, semicircularly

shaped - made my grip very unsteady and I couldn’t turn the plate, so for a while I touched its edge against the table. Some kind of

tension must have occurred, because three plates from this batch broke on the second firing.

I characterize the plates on the back - in addition to the studio logo, signature, and year of creation - with a letter, which indicates

the type of clay used. I give them consecutive numbers in order to keep track of which batch a given plate is from. I also make notes.

DL: Did you damage a lot? For what reason?

PS: At first a lot, when the plate turned out to be fine, it was a celebration. I was happy like a child. Nowadays I make about sixty

plates every year, and I’m currently working on number A450. There are two or three that crack in a season, because I mostly work

on the painting layer in the summer. The reasons for cracking are very different. One of them is the rather risky number of times

in the kiln, when I try desperately to save the artistic effect. I prepare the biscuits and designs in winter.

DL: Is it an expensive passion? And what about the commercial aspect?

PS: As for the commercial aspect, I have to mention the price of electricity when thinking about costs, and just for the sake of

argument, I should add that we are talking at a time of an energy crisis triggered by Russian aggression against Ukraine.

Translated by Elżbieta Rodzeń-Le¶nikowska

Dariusz Le¶nikowski

KATALOG

KATALOG

|

|

|

|