|

||||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

ENG

PL |

|||

|

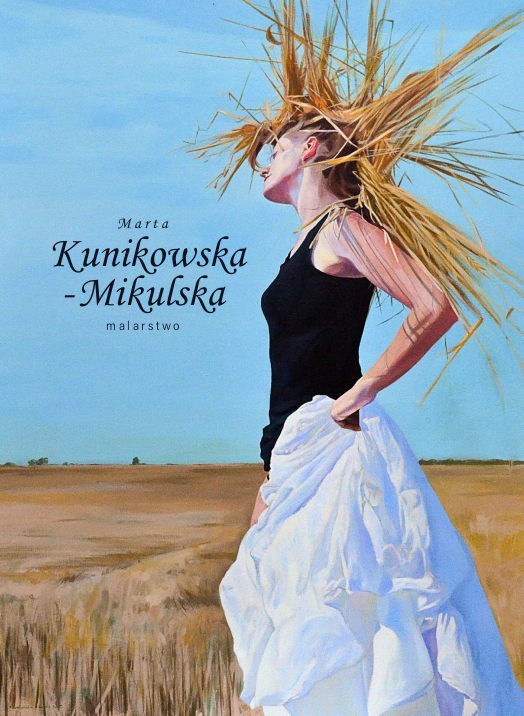

Marta Kunikowska-Mikulska » painting Angels and DemonsMarta Kunikowska-Mikulska’s paintings are astonishing, even though we recognize in her works thematic and formal approach already known from the history of painting, especially developed by Polish symbolism and, earlier, by the heritage of the Romantics, treated as an inexhaustible source of inspiration. What is captivating in the art of the contemporary artist is the fresh and unpretentious message. The author refers to the achievements of painting, which in a particular way referenced, among other things, the cultural depiction of a woman, an image torn between the vision of an angel, a gentle and idolised being, and the figure of a praying mantis, treacherous, leading to destruction and bringing death. In the paintings we recognize familiar motifs once taken up by Malczewski, Mehoffer, Okuń, Ruszczyc, Hofman or Chełmoński, noted in the titles, in the elements of clothing, in meaningful objects, movement-gesture formulas and selected artistic means. Even though we also find male figures in the paintings, or titles such as Chochoł (Capsheaf) or Czart (Chort), undoubtedly the heroine of the works is Woman (not necessarily Girl), in her physicality, corporeality, and, perhaps more importantly, in the metaphorical and symbolic dimension. The images are characterized by a kind of physical fullness, concreteness and vitality. The figures are the personification of female power, deriving both from her allure and the suspicious potency of goddesses and demons, known from folk beliefs and legends of a still pagan nature. A counterpoint to such representations are, drawn from Christian tradition, Madonnas – Madonna of the Fields and Madonna of the Herbs, in the depictions brought to European art by the Italian Renaissance. Let us recall again the legacy of the originators of Neo-Romanticism; they sought new paths leading to the spiritualisation of man, reaching for fresh sources of inspiration, such as for example esotericism or occultism. On the one hand, they were bewitched by the phenomenon of sanctity, and on the other − by the mysterious charm of magical procedures. Marta Kunikowska-Mikulska’s works are above all full of evocations of fantastic beings. These are female demons: Dziwożony, Rusalki, Poludnitse (Ladies Midday) or Mavkas (Souls of the Forest), which used to be an imaginary response to the fears and anxieties of existence tormenting man, often accompanying love failures, tragic breakups, dramas of family life, situations of loss or death. It is interesting, in the context of the subject matter taken up by the author of the works, that very often these disturbing spooks were, in folk beliefs, the personification of the souls of women who died just before or during the wedding, or shortly after getting married, also sinful creatures, those who died without confession, the condemned, such as unbaptized children. They bring doom to others, as if taking revenge for the injustice they have suffered, for their inability to achieve fulfilment, most of all as lovers, wives and mothers. Envying happiness, taking away peace of mind. Ambivalent characters − threatening, but also miserable, disguised in a new fantastic shape after tragic experiences suffered as humans. Often subjected to transformation as a result of rejection or crime. Like all fantasy figures, they function between life and death, the status of human and monster. It is worth recalling, which is also emphasized in feminist reflection, that a similar form of existence characterised witches (also crazy and hysterical women) who existed on the borderline of two worlds, the real and the post-sensory. Their image is a model of a woman who identifies herself as a being in harmony with nature, or who even rules it. Women operating in the realm reserved for witches, hysterics and the insane would thus experience – available to few – a special initiation and elevation. Some of the paintings could evoke the motif of the eternal opposition and conflict of the sexes, the struggle between the feminine and masculine elements, but in most of the paintings the artist does not refer to the popular Young Poland figure of the femme fatale, an interpretation of the nature of a woman with erotic overtones, but rather to an image typical of the experience of Polish folk culture, a symbolism rooted in respect for nature and fear of the unknown, a motif also often addressed by artists of the turn of the century. We should note that Poludnitsa or Dziwożona is often also the author herself, thus introducing autobiographical motifs into her works, a kind of intimate confessions concerning dilemmas, desires and disappointments. Female demons are creatures that inhabit forests, fields and ponds, dark nooks and crannies of marshy meadows and swamps. The peculiar nostalgic tone of the scenery, the stillness and silence the landscape is permeated with convey the metaphysical dimension of nature. Focusing in contemplation on a small fragment of nature, we discover its symbolic meaning and can grasp its psychic expression. It is in such staffage, in a landscape that takes on an almost mythological dimension, that the protagonists of the painting stories of the Lodz-based artist are portrayed. In folklore tales, the phantoms resembled ordinary, also elderly women, wore traditional clothes, or, on the contrary, wore light airy dresses, wove cornflowers, poppies and ears of grain into their fair hair for decoration – as in the paintings of the artist from Lodz (Panna Makowa (Poppy Maiden) draws our attention here, recalling even earlier than already mentioned, Pre- Raphaelite fascination with opiates, dream and death motifs). Sometimes the presence of apparitions was evidenced only by meaningful shadows cast on the wall of the house. However, the heroines of Marta Kunikowska- Mikulska’s painted (and graphic) representations are contemporary women, equipped with symbolic props originating from the art of modernism. Nevertheless, it should be noted that, although the sitters were undoubtedly people known to the author, these are not typical portraits. Equally important for the artist was not only to create a physical, credible image of the figure, but to create a mood sign and a symbolic personification, which is a metaphor for the human, complex and often miserable fate. Notable among the personifications are those that refer to the embodiments of the months and seasons, the figures shown among the attributes that characterise nature in its various temporal manifestations. Its successive incarnations pass away, giving way to the following ones, the old passes into the new, fasting is mixed with carnival, the retreat of famine is incanted and visions of abundance are evoked. The moment of transition is emphasised, creating a rite of eternal passage, a mystery play of life and death. In this context, paintings depicting pregnant women, shown in a state of expectation, hope and uncertainty, gain great importance. The motif of fertility (with the mystery of life in the background), one of the manifestations of biological female power, appears in these images. The archetype of motherhood is a symbol of a woman’s submission to social, cultural expectations, but at the same time a sign of her uniqueness and power, a testimony to the workings of the positive aspects of sexual forces inherent in the woman. Regardless of the metaphorical background associated with the subject, the figures appear on the canvases with distinctive props, such as flowers and herbs, straw toys, or even more significant, simple instruments made of clay (cock-whistles). As attributes of fantastic beings, they take on a magical dimension, making alluring mysterious sounds, beckoning men and foreshadowing fatal dancing (as in some versions of the Rite of Spring celebrated in various regions of the world) and singing, and finally screaming. A distinct group of paintings are those that expose images of women who, in a more intimate form that does not impose additional connotations, try to express their emotions: suffering, anxiety, a sense of loneliness, reverie, perhaps also a kind of embarrassment. They subject themselves to psychological introspection, exploring the mysteries of destiny. They simultaneously personify common existential fears and obsessions, sadness and pain of existence, inherent to all. The women, somewhat absent, lay down as if they were to sleep, seemingly only resting, curled up in an embryonic position that guarantees isolation and safety. It also happens, however, that some of the depictions are not free from reserve and humorous associations. The figures portrayed by Marta Kunikowska- Mikulska in her paintings through spatial context, clothing and props embody the old symbolic beings present in beliefs and legends. As pictorial motifs they usually function in isolation. This is, of course, primarily a privilege of the portrait convention. However, it is worth mentioning that single women (maidens, forsaken women) or those who are different, unconventional (herbalists, healers, “Wise” or “Knowing”) in the area of women’s studies do not have a pejorative character, on the contrary, they are those who − connecting the spheres of reality that have been separated so far − create an original sphere of female culture. On the other hand, in society, a woman who does not conform to stereotypes, for some reason does not accept the cultural role assigned to her and is rebellious, becomes cursed, becomes an outsider to society, is most often treated as a stranger, an Other, and may be suspected of either mental illness or consorting with the devil. Among other things, such judgment also echoes beliefs about the feminine nature of creatures such as Rusalki, Zmory or Poludnitse. Marta Kunikowska-Mikulska’s works are characterized by excellent craftsmanship. The artist paints very realistically, drawing on the poetics of “extraordinary ordinariness”. Portraits, referring to the classical Renaissance tradition, are based on the central composition, but most of them are representations in which the artist employs unusual ways of depiction, constructed with unorthodox perspectives. She uses a raised or lowered point of observation and narrows the spatial sphere of the image. She uses close-ups, “crops” motifs. She builds her synthesising stylistic formula, supported by decorative stylization. The artist is not afraid of colour, she often operates with a broad, vivid colour patch; some of them, like apla, allow to more strongly accentuate the main pictorial motif, sometimes even to monumentalise it. Intense light weakens the realistic nature and unambiguity of vision. Marta Kunikowska-Mikulska is also the author of graphic works made in lithography and stone engraving. In her portraits, the artist shortens the perspective even more, works in a greater close-up, crops the figures to the fragments of the head or face, and intensifies the expression. The tool of her creation process this time is the line, free, flowing, in many cases sort of Art Nouveau line. It is significant here that − realizing the power of the wavy line − she abandons colour in these works. It is a conscious decision taken in view of this graphic technique, which, after all, is considered the most painterly one. Marta Kunikowska-Mikulska’s works are not mindless, efficient repetitions of established conventions, but expressions created from the point of view of a contemporary woman, messages that are both universal and very personal. The old contents have been disguised in a contemporary costume; the past provenance and reality of these paintings fit perfectly into today’s perspective on women and the phenomenon of femininity, into reflection on the perception and depiction of women in contemporary culture. Thus, the artist refers to traditional motifs not only out of respect for the achievements of the great Polish painters, but also in order to impose into the perception of the works today’s contemporary perspective on the familiar, already assimilated iconographic motifs. Dariusz Leśnikowski Translated by Elżbieta Rodzeń-Leśnikowska

|

|

|||

|

HOME | NEWS |

EXHIBITION | ARTISTS | CONTACT |

|||||