|

|

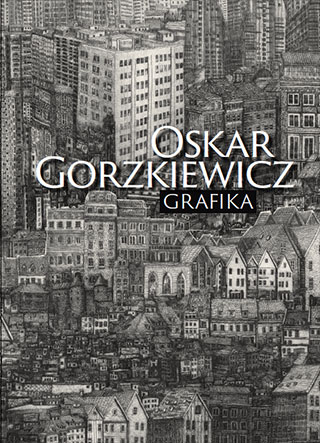

Oskar Gorzkiewicz »

GRAFIKA

Oskar Gorzkiewicz’s atlas of (im)possible cities

For two centuries, a growing process of urbanization has been observed around the world.

In some countries almost all people live in cities today. No wonder that they are becoming the

subject of research, theoretical and practice-oriented reflections from different perspectives:

historical, ethnographic, cultural and urban planning. They are also an important theme in art.

Homo urbans triumphs.

The spaces of Oskar Gorzkiewicz’s graphics are simultaneously possible and impossible. In the

process of creation they are deconstructed and constructed anew. The structures that fill them are

quasi-organic in character. They flourish, grow, going beyond the limits of the established frames.

They give the impression that they lead a life for themselves. They seem to be self-sufficient.

Gorzkiewicz’s graphic images are only illusions, chimeras, stage designs. Reality is mixed with

fantasy there. The city, civilized space appears in them like a complicated, labyrinth-like moloch

devouring its inhabitants. We feel lost in it. We have a similar impression when we look at the

reconstructions of the ancient city-palace in Knossos, or when we try to wander around the

fantastic world that is brought out of Giovanni Piranesi’s imagination.

The city is a world in miniature. It stands for the whole reality. It is its model. Its space is a crazy

vision of a consolidated micro-world of districts, houses, backyards and alleys. To paraphrase

Dostoyevsky, are Oskar Gorzekiewicz’s cities ‘the most theoretical, imaginary cities in the world’?1

Somewhere beneath the layers of minor stories of each of these places are hidden depths

of great history: the fate of countries and rulers, heroes and traitors, geniuses and ordinary

bread-eaters. Artists. Their traces can be found under the cobblestones of streets and squares,

in canals and cellars. A specific ‘urban reading’ allows us to go deeper into this history, lets us

outline the cultural topography of each place.

These are, in a way, magical spaces. Oskar Gorzkiewicz’s imagination creates new, nonexistent

cities, each with its own unique character. The codes hidden in them can be read and

understood in many ways.

The phenomenon of the city is that it is a multi-layered and multidimensional structure, which

is not easy to fully describe and define. Its tissue consists of compositions of buildings, streets

and squares. But not only.

Urban development, public spaces, technical infrastructure, greenery and water reservoirs, legal

and urban planning regulations, conventions, culture, social systems, as well as relations between

them, their size, distances from each other, division into districts, quarters and plots, all this creates

a synergic functional system.2

The life of the city is associated with a continuous process of growth of successive layers, both

material and intangible. When this continuity is interrupted, the city loses its genius loci.

Visions created by Oskar Gorzkiewicz are not very comforting. His cities are deprived of all those

features that guarantee human safety. It is difficult to recognize the space, to be well-orientated

in it. There is a lack of welcoming public space, streets and squares organizing life. The city zone,

which is difficult to define, hardly legible, deprives people of a sense of stability and comfort.

It is defined as lost space.3

As in the surrealistic practice, Oskar Gorzkiewicz takes out pictorial elements from the proper

context and places them in the next, objects are given new meanings. These are artificial

constructions – contaminations, collages. On the surface everything seems to be consistent

there. One can easily recognize tenement houses and blocks of flats, notice windows and

gates, domes and chimneys. We realize, however, that the artist himself determines spatial

proportions, relations between the size of objects, perspectives. Within one work he repeatedly

breaks the logic of the message. He introduces apparent distortions. Sometimes we have

the impression that centuries later Baroque illusionism in marriage with fantasy reigns again,

embodied for example by great wall compositions by Andrea Pozzo; in his frescoes based on

the use of one point linear perspective, the picture seems to be perfect only when we look

at it from a specific, carefully defined place, otherwise the buildings collapse, cornices crack,

columns break, the world looks like seen in a distorting mirror. In some Visions of the City

by Gorzkiewicz, architectural structures occupy unusual places: domes are deformed, walls

are suspended in space, reality is subject to circulation, it is lost in alogicality. In the spectacular

graphics by Oskar Gorzkiewicz, such architectural features as invariability, stability and stillness have

lost their sense, since today they are more and more often changeable, unpredictable and dynamic.

The artist creates the depicted world based on photographs of real, existing buildings,

completes it by drawing the missing motifs, juxtaposes them together. One of the most

important tools organizing the whole is the contrast of elements used. The artist combines not

only various spaces, objects of various proportions, forms and textures, but also cultures and

styles, functions and meanings, past and present.

Gorzkiewicz pays great attention to creating a convincing illusion of space. This effect is

achieved not only through the use of three-dimensional representations that gain a semblance

of plausibility, or their appropriate juxtaposition in order to create an impression of depth, not

only thanks to the value contrasts and other means of plastic shaping, but above all through

the use of the author’s original method of multi-matrix printing within the intaglio printing

techniques. Gorzkiewicz juxtaposes sheets with objects cut ‘after drawing’ side by side, above

and below each other; he does not print from several matrices one after another. The matrices

have different character, different properties; some are more linear, drawing; others are more

flowing, plane-like. Their contrasts enhance the impression of depth in the graphics.

Relief, which is created as a result of layered overlapping of matrices, is physical, tangible – it

makes the author’s visions credible. All graphics have an open composition consisting of

layered buildings and structures. A specific ‘thriving architectural poem’ is created, characterized

by the growth and multiplication of motifs (the artist does not conceal his fascination with

wild, disordered housing estates, emerging in metropolises as a result of spontaneous human

activity). The visual values of the city are defined not by one, but by whole groups of buildings.

To evoke emotional values it is important to differentiate their scale, proportions, their

composition, the variety of materials used, colours, texture of the surface, the effect of - often

centuries-old - layers and changes. The urban development in Gorzkiewicz’s visions extends

all the way to the limits of the work, going beyond its frames in all directions. It is probably

connected somewhere in space with other, similar ones. The structure of the whole remains

non-hierarchical and non-centralised4.

We get images of partially distorted, disturbed reality, filled in with a multitude of

representations; their fragments are shown from different perspectives, but surprisingly they

create very convincing visions. These are personal, creative comments on a given view, not

copies of real spaces. Oskar Gorzkiewicz implies that it is a mystification. He leaves white lines

that appear on the border of individual matrices, he does not continue, some motifs in space,

as it is logically suggested, he points to the sources of iconographic inspirations.

If the echoes of surrealistic poetics can be recalled here once again – in these graphics

there is not only a reference to the very method of presenting things in new contexts, but

also a characteristic feature that was typical of the metaphysical variety of this trend in art,

consisting in creating a liberating feeling of anxiety, uncommonness, strangeness of wellknown

objects.

The works are imbued with an abundance of artistic means of expression. Drawing plays

a major role in them. It is so important that the artist prefers to engrave surfaces with rows

of parallel needles and create the impression of a uniform surface rather than to etch whole

planes. Lines of varied density, which make up a given motif, are a source of diverse textures.

They run in different directions, intersect, smoothly permeate on the border of different

surfaces, creating tonally varied compositions.

The creative work is used by the artist not only to convey important intellectual and visual

content, but it is also a testing ground for him to take up technical and technological issues.

Each action is preceded by numerous trials concerning the used materials and tools, the time

of etching, etc. The works are printed from matrices made of various types of metal sheets

- steel, zinc-titanium. Each of them involves a different intaglio printing technique (etching,

ferrotint, etching on iron), some of which are unpredictable in terms of the assumed effect.

The results obtained through the experiments correspond to the intended, specific formal and

imagery needs and, consequently, to the adequate conveyance of emotional and intellectual

content. The construction of the presented world complies with the construction of the graphic

work, which in turn is a reflection of the thought process and the process of creation of the

work by the artist.

In the renditions of fantastic cities created by Oskar Gorzkiewicz, there is no room for their

inhabitants, although we suspect that they hide behind windows, in the gates and in the

basements. Contemporary cities have changed their character. The phenomenon of the new

situation reflects the notion of the space of flows, which ‘does not substitute geographical space.

The point is rather that by selectively combining places, it changes their functional logic and

social dynamics’5.

Until recently, the dimension of urbanity was associated with a geographically determined

place. People still live in some places, but the bonds between them are currently difficult to

attribute to a specific area. The new dimension of life is no longer based on staying in a physical

space, but on immersing in a global network filled with information technologies. Both time

and space are being transformed in them.

--------------

1 The Russian writer described St. Petersburg as such in Crime and Punishment.

2 A. Prokopska, A. Martyka, Miasto jako organizm przyjazny człowiekowi, „Budownictwo i Architektura” 2017, 16 (1), p. 165.

3 See R. Trancik, Finding Lost Space, Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York 1986.

4 See U. Eco, Vertigine della lista, Rizzoli, 2009. Quoted after Polish translation: U. Eco, Szaleństwo katalogowania,

transl. T. Kwiecień, Rebis, Poznań 2009, p. 240-241.

5 F. Stalder, Manuel Castells, The Theory of the Network Society, Polity Press, 2006. Quoted after Polish translation: F. Stalder,

Manuel Castells. Teoria społeczeństwa sieci, transl. M. Król, Wyd. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, Kraków 2012, p. 170.

Dariusz Le¶nikowski

Transl. Elżbieta Rodzeń-Le¶nikowska

KATALOG

KATALOG

|

|

|

|